Amid controversy over the use of facial recognition by law enforcement, records show that 10 employees from the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office signed up for trial versions of a technology called Clearview in March and June.

Clearview is a facial recognition startup that aggregates photos from the open web into a database marketed to law enforcement. The platform has been met with widespread criticism — from researchers, privacy advocates, Democratic lawmakers and many of the social media companies it relies on for data — for infringing on individuals’ privacy rights. Supporters, however, say the technology is an important tool to help solve crimes.

Email records obtained by PublicSource via a public records request show:

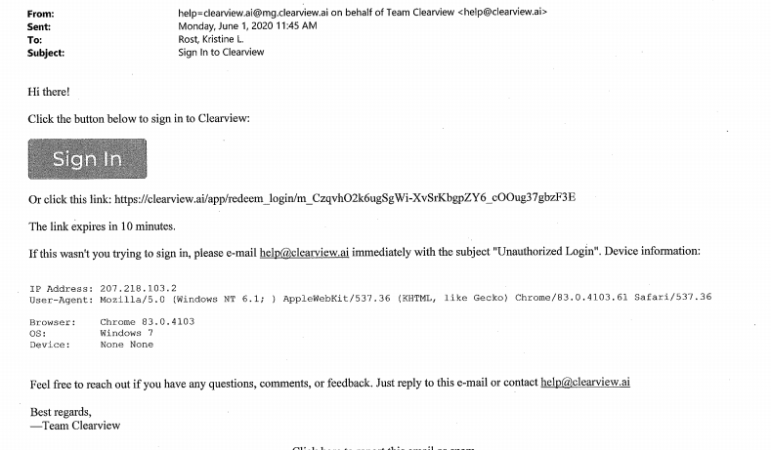

- Email communication between Clearview and AG employees began in March when six employees received login information for trial accounts or invitations to sign up for trial accounts. It is not evident from the records whether employees logged in to accounts at the time.

- Emails between employees of both offices resumed June 1, the Monday following Pennsylvania’s first protests over the death of George Floyd.

- Four additional AG employees received emails from Clearview with login information or invitations to sign up for trial accounts between June 2 and June 25. Three employees also received emails indicating that there were attempts to log in to their trial accounts between June 1 and July 8.

- The records, however, do not indicate that the technology was used in relation to any protests or related cases.

“The Office of Attorney General did not purchase this software and our prosecutors have not used it in any of our cases,” a spokesperson for the office wrote in an email to PublicSource.

“The office accessed a free trial of this emerging technology to understand its capabilities, limitations and hazards.”

According to Clearview founder Hoan Ton-That, the technology “is used only by law enforcement for after-the-crime investigations to help identify criminal suspects. It is not intended to be used as a surveillance tool relating to protests or under any other circumstances,” he wrote, through a spokesperson, in an email to PublicSource.

“If we were to discover that a law enforcement client in fact used Clearview AI inappropriately, their account would be terminated immediately,” Ton-That added.

The AG seat is contested this election, with Attorney General Josh Shapiro, a Democrat from Montgomery County, up for reelection.

The office is one of nine local, state and federal law enforcement agencies in the Damage Assessment and Accountability Taskforce [DAAT], a Pittsburgh task force launched in early June to investigate “people who have attacked journalists, looted business, caused property damage and committed other crimes such as arson” in relation to protests.

The Pittsburgh Bureau of Police [PBP] used facial recognition through the statewide JNET database to identify the suspect of a crime related to a June Black Lives Matter protest, a previous PublicSource investigation found. Public Safety spokesperson Cara Cruz wrote in an email to PublicSource that PBP does not have access to technologies besides JNET. She did not indicate if other DAAT agencies used additional technologies in the task force’s investigations.

Some law enforcement officials have sung the praises of facial recognition as a useful investigative tool. “Nobody can dispute that it makes communities more safe. It simplifies law enforcement duties, it simplifies the research process, it saves money, it saves time,” said Jonathan Thompson, executive director of the National Sheriff’s Association in a September interview with PublicSource.

Yet privacy advocates, researchers and cybersecurity professionals PublicSource spoke with objected to law enforcement’s use of Clearview and facial recognition technology in general.

Freddy Martinez, a policy analyst at Open the Government who aided in a January New York Times investigation of Clearview, said the company aggregates “highly profiling information” such as where an individual works, the Facebook groups they belong to and information about their family members.

“There’s no consent. It could be photos that other people have posted of you online,” he said in a July PublicSource interview. “So you might not even know that a picture of you exists, and you could be having Clearview collecting that data and selling it to law enforcement.”

Clearview, a facial recognition startup that scrapes the open web for images to add to its database of billions of photos, has drawn intense criticism. Tech experts that PublicSource spoke to in July called the technology “Black Mirror’-esque” and warned of its privacy implications and potential to exacerbate existing disparities in policing.

The company markets itself as a tool for law enforcement and says its system has helped investigators track down “hundreds of at-large criminals,” including pedophiles, terrorists and sex traffickers. “Clearview AI is widely used and relied upon by law enforcement because it has helped solve many crimes, such as murder, child exploitation, and human trafficking that would not have been solved otherwise,” Ton-That wrote to PublicSource.

Emily Black, a Ph.D. student in computer science at Carnegie Mellon University and member of the Coalition Against Predictive Policing, expressed worry that the looming presence of surveillance technologies like Clearview could impact whether individuals feel comfortable exercising their First Amendment rights to free speech and assembly. “I think that the loss of our privacy, the loss of your ability to be just sort of one in a crowd, has an effect on your ability to stand up for your rights because you have a fear of being targeted,” she said.

In 2015, Baltimore police used facial recognition to identify and arrest individuals during protests over the death of Freddie Gray.

Facial recognition has also led to a small number of known wrongful arrests.

Yet law enforcement officers told the New York Times that Clearview was unrivaled in its ability to identify criminal suspects, even allowing dead-end cases to be reopened. The app has been helpful in solving crimes from shoplifting to murder.

The Attorney General’s office isn’t the only Pennsylvania law enforcement agency to have dabbled with Clearview. Trial accounts were linked to the email accounts of four employees of the Allegheny County District Attorney’s Office, email records from February and March show.

Elsewhere in the state, the Philadelphia Police Department ran roughly 1,000 Clearview searches during a trial period last year, while police in Wyomissing, in Berks County, paid for a Clearview account. “We got it as another investigative tool that our investigators wanted to use and see if it benefitted us in solving crimes for victims,” Wyomissing Police Department Lieutenant Thomas Endy told PublicSource.

In September, Pittsburgh City Council passed legislation regulating the use of facial recognition by city law enforcement, while Allegheny County Council introduced a similar bill on Oct. 6. There are no statewide or federal regulations related to its use.

“Regulation is not only due, it’s past due, because systems have grown in kind of the negative space left by the lack of regulation,” Black said. “[N]ot only do we need to address things that might happen in the future, but I think we also need to take a step back and understand the extent of the facial recognition technologies that are being used right now… and how we want to regulate those that are in existence.”

Shapiro will face three challengers in November: Republican nominee Heather Heidelbaugh, of Pittsburgh; Green Party candidate Richard Weiss, also from Pittsburgh; and Libertarian Daniel Wassmer of Pike County.

“I’m pretty clear that I find the expansion of the police state to be indicative of the total erosion of personal liberties,” Wassmer wrote in an email to PublicSource. “…About the last thing I would want to see in the hands of overly zealous authoritarians would be the use of such technologies.”

Weiss said facial recognition “could be an investigative tool” but that it “is not foolproof and by itself should not be considered proof positive for convictions.”

Heidelbaugh did not respond to requests for comment.

Juliette Rihl is a reporter for PublicSource. She can be reached at juliette@publicsource.org or on Twitter at @julietterihl.

This story was fact-checked by Emily Briselli.